Researching Race and Community in Asia

Sharon Yoon

Keough School of Global Affairs

Growing up as a second-generation Asian American in New Jersey, Sharon Yoon lived in a home that served as a bustling community hub. Her Presbyterian minister father, who immigrated from Korea to the United States as a graduate student in the late 1970s, helped the Korean immigrants who came to his church with their everyday needs.

“People looked to my father to help them translate documents, find lawyers, communicate with police officers and provide marital counseling,” said Yoon, assistant professor of Korean studies in the Keough School of Global Affairs. “Our home was a place of rest and affirmation, a safe space.”

But then after nearly eight years, it all fell apart. The tight-knit church community disbanded amid internal disagreements, and Yoon’s father suddenly became unemployed. Her parents tried to make ends meet, using their retirement savings to start a small pet supply store, but the business was unprofitable and closed within a year of opening. After a series of attempts to find a new career after serving as a minister for 25 years, her father fell into a deep depression. Witnessing his struggle played a critical role in shaping Yoon’s decision to study Korean diasporic communities as a graduate student at Princeton University, where she earned a doctorate in sociology.

“Much of my research is intertwined with my lifelong struggle to try and process many of my childhood experiences of helplessness,” Yoon said. “These formative memories made me want to understand why certain types of immigrant entrepreneurs were able to succeed against all odds, and why others failed even though they seemed set up for success.”

Yoon, who came to Notre Dame in August 2020 from a faculty position at Ewha Womans University in Seoul, has produced a rich body of research that focuses on how race and identity politics function among marginalized communities, primarily those in Asia, and analyzes how people are able (or unable) to mobilize resources to advance their economic, social and political goals.

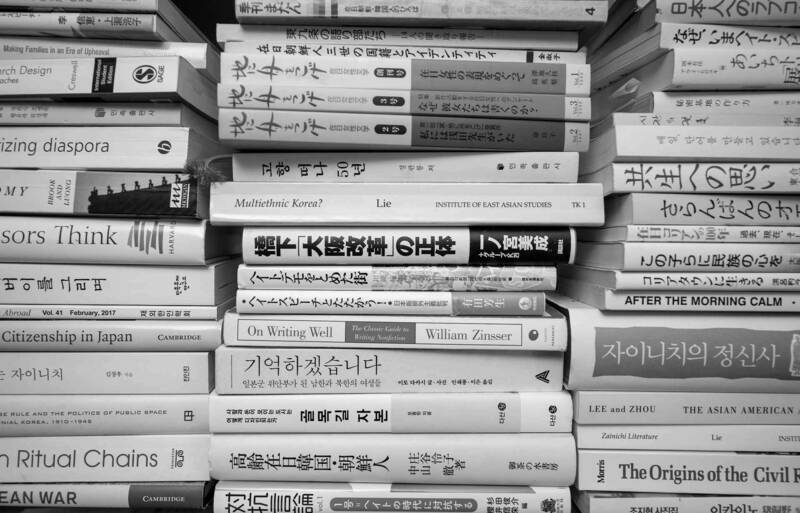

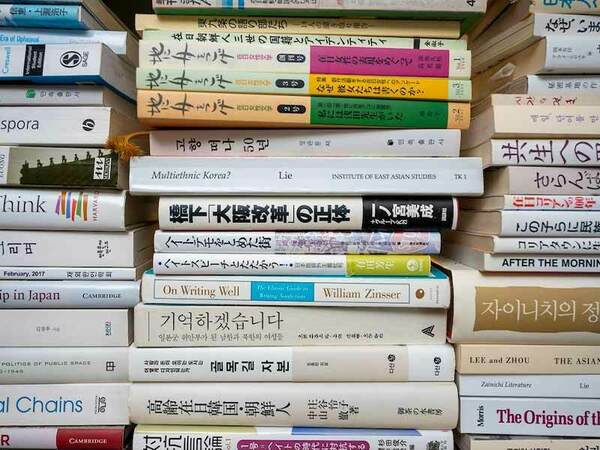

To gain these empirical insights, Yoon employs ethnographic methods to observe everyday life, and has spent several years immersed in the marginalized communities at the heart of her research. As part of the fieldwork for her first book, “The Cost of Belonging: An Ethnography of Mobility and Solidarity in Beijing’s Koreatown” (Oxford University Press), Yoon taught English to Chinese rural migrants of Korean descent at a Korean underground church, worked as a store clerk for a Korean clothing boutique, interned as an English translator for a major South Korean conglomerate and played the piano for a South Korean state-sanctioned church in Beijing.

“By observing daily interactions, ethnographers try to make sense of structural problems people face,” said Yoon, a faculty fellow in the Keough School’s Liu Institute for Asia and Asian Studies. “People discuss their problems as individual problems. Many of the South Korean entrepreneurs I met would point to their specific experiences, saying, ‘This is why I failed,’ but as an ethnographer, it is my job to shed light on how broader patterns in labor markets, migration policies and access to resources influence an individual’s ability to thrive economically, socially and politically. In Beijing, I started to see how the vast majority of South Korean migrants struggled to achieve upward mobility not because of a personal shortcoming, but structural barriers that placed them collectively at a disadvantage.”

In conducting research for “The Cost of Belonging,” Yoon wanted to understand how immigrant entrepreneurs were able to achieve socioeconomic mobility by building small businesses that catered to the Korean expatriate community in Beijing, largely because she grew up around Korean entrepreneurs as a child.

“I watched many people silently toil long hours in precarious conditions in hopes of achieving the American dream,” Yoon said. “This eventually became my parents’ experiences as well. In the process of writing about Korean entrepreneurs in Beijing, I was able to intellectually come to terms with the pain of my own past. Research has provided me a safe space to tease out the trauma I personally experienced as a child of immigrants.”

Yoon’s next research project will take her to Korean neighborhoods in Osaka, Japan. Funded by a grant from the National Endowment for the Humanities and the Japan-United States Friendship Commission, the project focuses on how Korean minorities in Japan mobilize political resources within their communities to form anti-racist movements. Titled “Social Media Activism and the Fight against Hate in Osaka’s Koreatown,” the project will analyze how social network sites have opened up new avenues for civic engagement in Japan. In particular, Yoon’s project analyzes how physical environments such as Korean enclaves shape the ways activists share information and resources to effect legislative change.

Once completed, Yoon hopes her research in Osaka will provide helpful data for countering racism in other parts of the world.

“Structurally what is going on in Japan is happening all over the world,” she said. “People are mobilizing from the bottom up through the internet. We see this battle between the left and right playing out right before our eyes in sometimes violent ways on the streets. I believe that it is critical to better understand how social media is changing the world of politics for better and for worse.”

“My research is motivated by my own curiosity, and I’m able to form relationships with people on the other side of the world who are really suffering and help their voices be heard.”

Though Yoon grew up in the United States, she was formed as a scholar by her time in Asia. As an undergraduate at Dartmouth, she spent most of her college years studying abroad in Korea, Japan and China. Before her first faculty position in Seoul, she worked as a postdoctoral fellow in Japan for two years. She speaks fluent Korean and Japanese and is proficient in Mandarin.

At Notre Dame, Yoon brings all of this expertise to the classroom by teaching Race in Asia, an elective course for the Master of Global Affairs program, and Connecting Asia, an undergraduate elective. Though she’s taught at Notre Dame for less than two years, she already has become a sought-after mentor, especially by students from disadvantaged backgrounds.

“My students need more minorities who look like themselves who are in positions of authority,” Yoon said. “They tell me about their personal struggles and backgrounds — I think they are in search of people to talk to who make them feel safe and validated.”

Yoon committed herself early in her career not only to helping her own students, but to contributing to the greater good globally, and these commitments serve as both a lodestar and a motivating force.

“In many ways I have a dream job,” Yoon said. “My research is motivated by my own curiosity, and I’m able to form relationships with people on the other side of the world who are really suffering and help their voices be heard. Listening to them and seeing how they give of themselves for their community gives me a sense of hope that extends beyond the gratification I feel from any particular publication. It’s that sense of hope that sustains me.”