Computer Scientist’s Character Forged in Homeland War

Tijana Milenkovic

College of Engineering

Tijana Milenkovic was in the fourth grade in Sarajevo when the war that broke apart the former country of Yugoslavia erupted in 1992.

She remembers avoiding the windows for fear of snipers and catching rainwater to take showers. Enduring a 20-mile exodus from the city that took nine hours to pass through military checkpoints. And walking two hours through woods potentially littered with hidden land mines.

“As a woman in engineering, you have to have a very thick skin. I think all of it prepared me for who I am.”

Yet Milenkovic said simple meals best illustrate what her family went through.

“We were without proper foods for months,” she said. “We ate rice without any spices, and pasta without any spices. To this date for 30 years now, I cannot eat rice. I can’t. It’s just my war trauma.”

She credits those crucible experiences, along with role models like her mother, with making her stronger, equipping her to land where she is today as the Frank M. Freimann Collegiate Professor of Engineering at Notre Dame.

“It’s made me have a really thick skin,” Milenkovic said. “As a woman in engineering, you have to have a very thick skin. I think all of it prepared me for who I am.”

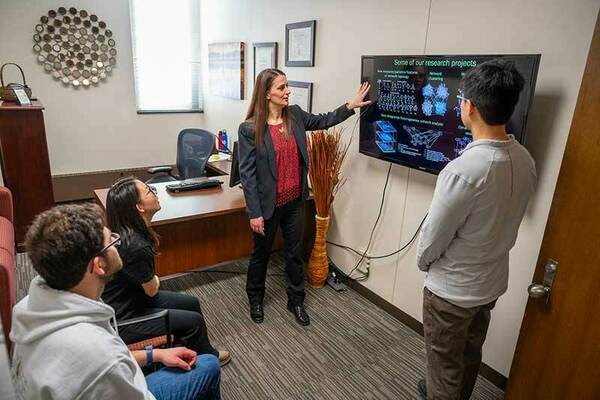

Milenkovic, a computer scientist, directs the Complex Networks Lab, which solves challenging problems in the fields of network science, graph algorithms, computational biology, health and well-being, and social networks. She also takes a special interest in mentoring students, with a focus on helping women and minorities overcome the kind of obstacles she has faced.

If others sometimes find her ambitious or intense, they might want to consider their reaction in the context of what Milenkovic survived. For instance, when the pandemic hit in 2020, many people wondered how they would endure the boredom and loss of social connection. Her response was different.

“The first thing that went through my head,” she said, “was if I lose power, which furniture will I be cutting up for firewood, in which order, to use for heating and cooking.”

The civil war that tore Yugoslavia into ethnic and religious factions lasted for nearly four years. After six months of living under siege in Sarajevo, her mother fled their city home to take Milenkovic and her brother to their grandmother’s house in a village outside the city. When her father died in the fighting, the family fled again to an aunt’s home in Belgrade, Serbia.

Milenkovic returned to Sarajevo after the war and finished high school, but she had to decide whether to study math, computing or biology at the University of Sarajevo. Under her home country’s free education system, she earned an undergraduate degree in electrical engineering and computer science and decided to go abroad to advance her education.

“In my home country, based on my name, people can tell what nationality and what ethnicity I am, and obviously what gender I am,” she said. “I often felt discriminated against.”

The United States represented an opportunity for a better life, because she figured everybody there emigrated from somewhere else. At the University of California, Irvine, she chose computational biology, an emerging subfield of computer science. She completed her doctoral work in three-and-a-half years.

Milenkovic came to Notre Dame in 2010 as a faculty member because the offer fit her research interests. “There seemed to be a huge interest to form a strong computational biology initiative on campus and that there would be tons of potential to work with biologists, which is critical for me,” she said.

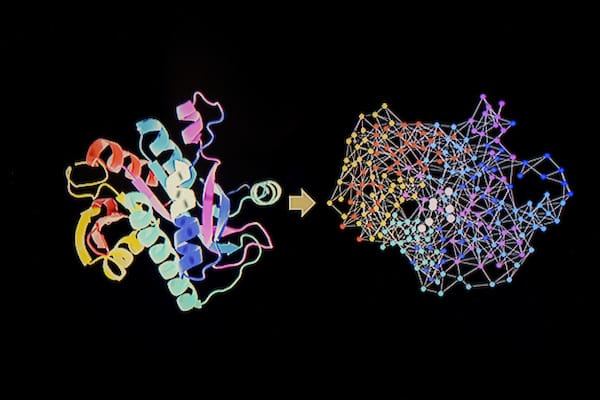

“Network science is one way to describe my research, and computational biology is another one,” she said. “My research spans computer science and mathematics and biology, the three areas I was debating what to get a degree in. It turns out there are no more hard lines between areas, so I ended up doing my dream job.”

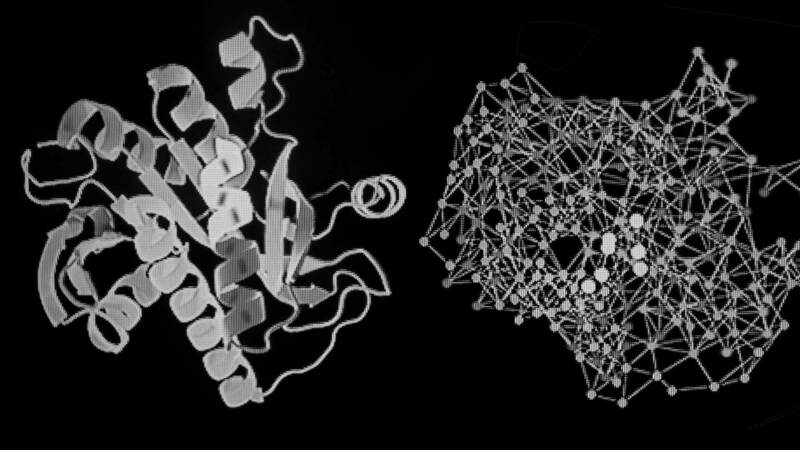

Her research deals with network algorithms, which she explains this way: Different networks — whether a power grid, transportation system, human cell or even social relations — all can be modeled mathematically to capture the relationships between the parts that make up the network.

Algorithms, she said, are computational approaches that take input data and create a prediction for an outcome the user is interested in, which can be anything from the likelihood that a gene causes cancer to a movie that person may like.

Many complex diseases, from heart attacks to Alzheimer’s, occur more frequently as people age. Because there are practical and ethical challenges to biomedical strategies of studying the molecular causes of human aging, Milenkovic instead uses computational approaches to identify aging-related gene pathways.

“The goal of my work is to develop novel computational approaches or algorithms that will take the variety of data available about the human species or a particular individual and try to make predictions and improve human health,” she said.

For example, she and collaborators worked with Notre Dame student health data to predict mental health status. Hundreds of students were given cellphones and Fitbit monitors to gather anonymized data about their social networks and health behaviors.

Milenkovic knew the students’ mental health status from surveys. Her objective was to evaluate the ability of her computational approaches to predict the mental health information using social connections and health statistics. Her specialty is to evaluate the data’s potential and to create better predictions for whatever her collaborators want to learn.

“You must demonstrate your method is better than if you were making predictions at random,” she said. “And you’re better than every other approach out there for the same purpose.”

Whether it’s solving network problems or tackling education diversity issues, Milenkovic approaches her work with a survivor’s passion.