A Measure of Justice

Maria Maciá

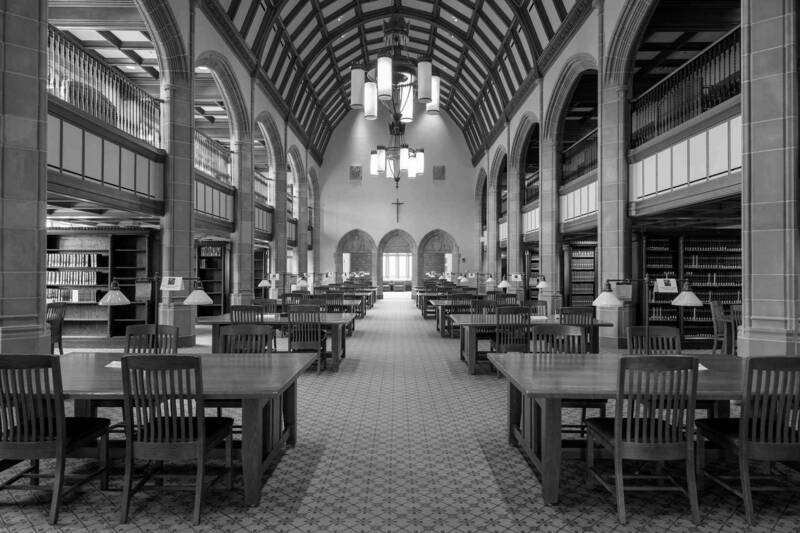

The Law School

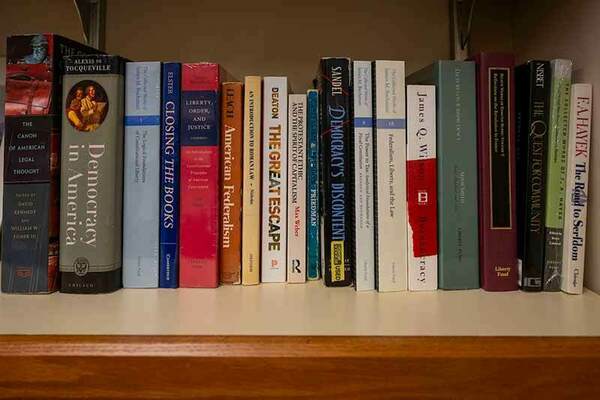

Professor Maria Maciá is trained as a lawyer and an economist. Her research uses empirical evidence — statistical analysis and other substantiating support — to determine how laws intended to align corporate actions with social welfare are working. Those conclusions can then be used to help tailor corporate regulations to address better the problems they are intended to address.

Maciá received her J.D. and Ph.D. in economics from the University of Chicago. She came to Notre Dame Law School as a visiting professor during the 2019-20 academic year and became an associate professor in 2021. She now teaches law and economics, antitrust law and corporate finance classes to law students. She was led to academia rather than practicing law because she enjoys teaching these topics to law students: she believes that exposing future lawyers to economic principles will help them understand the law better and discover ways to improve it. She also wanted to contribute to policy discussions about how we should regulate corporations.

“Laws can sound really great in theory, but they are a work in progress, and it is important to know how they are playing out on the ground.”

An interest in both law and economics was instilled in Maciá when she was very young. She was profoundly influenced by her father, who was 14 when he immigrated to the United States from Cuba a year before his parents could. She grew up hearing stories of what life was like in Cuba and the impact of Fidel Castro’s policies on his family.

“It was a drastic action to leave his parents and uproot his life. So I understood how severe the situation was for his family and realized from a young age that economic and legal systems have serious consequences,” she said.

In college, she learned about the political situation and inequalities in Cuba prior to Castro, and how his policies were a response to serious social problems.

“It was an interesting puzzle to me — resolving how Castro’s reforms seemed so well-intentioned with their effects on my family. It showed me how important it is to ask what the empirical consequences of policies are,” she said.

This is an approach she brings to her research. One area of research she is currently undertaking examines policy responses to the link between human rights violations and the mining of tin, tantalum, tungsten and gold in the Democratic Republic of Congo. Consumers around the world buy products derived from these minerals, and in doing so indirectly finance militia groups in the Congo. Recent laws require certain companies to provide consumers and investors with more information, through disclosures, about where their inputs originate, with the hope that consumers and investors will punish the companies that use less ethical sourcing.

“I look at how consumers and investors are responding to the disclosed information. I use my empirical training to show that in general, people are not responding to the information in the way that the law needs them to for it to work,” she said. “Laws can sound really great in theory, but they are a work in progress, and it is important to know how they are playing out on the ground. By digging into the data and identifying the more narrow circumstances in which consumers actually purchased less from the companies with more problematic sourcing practices, I can suggest ways to tweak the current laws to make them more effective.”

To Maciá, what is most exciting about the scholarship side of academia is the opportunity to contribute to real solutions. She looks for opportunities to combine her legal and empirical training to make an impact. For example, in her legal studies, Maciá was exposed to the fact that different courts at different times changed the legal rule to make it easier to prove discrimination in mortgage lending. This creates an opportunity for a standard analysis used in economics where the researcher looks for a difference in outcomes in places where the law changed compared to those in which it did not. As a result of her knowledge of the intricacies of the legal rules, she has been able to make use of an opportunity to understand mortgage discrimination that other economists have missed.

She said, “I look at what the data teaches us about how banks respond when the legal rule changes. If you measure discrimination one way, by looking at how lending institutions treat a minority applicant compared to others, it seems like discrimination is reduced when the legal rule changes. But I find that banks do not increase the number of loans to minority populations. So the discrimination has likely moved to more difficult-to-detect levels, showing how difficult it is eradicate.”

Mortgage discrimination and ethical sourcing of inputs are the kinds of issues Maciá looks for, where the laws really matter. Because the stakes are so high, she says it is so important to get these laws right. “I get a lot of meaning out of contributing and providing information that can be used to improve our laws.”

“It is an honor to be there with someone at the stage of their life when they are trying to figure out what they want to do and how they want to do it, and to help guide them in that process.”

Maciá finds it particularly meaningful to have the chance to work on these sorts of projects while getting to teach as well. She grew up in a family of teachers and saw people who were passionate about teaching. Her father is an engineering professor and her mother is a religious education director who helps train catechists to use Montessori methods in educating children about their faith. Maciá saw how their work mentoring and training others in areas they care about deeply energized them. She says many of the people in her life that made a difference were teachers.

Now as a professor herself, one of the things she enjoys most about teaching is mentoring students, including helping them make professional decisions — something she is able to draw on her own experiences for. During graduate school, she sought out a variety of summer work opportunities, working at a large law firm in New York, at a small law firm in Phoenix and in the Antitrust Division at the Department of Justice. She enjoys talking to students about these experiences and helping them think through where they should start out their legal career, including what legal opportunities might be particularly fulfilling for students who love economics.

“It is an honor to be there with someone at the stage of their life when they are trying to figure out what they want to do and how they want to do it, and to help guide them in that process,” she said. She also found clerking for Judge Andrew Hurwitz on the 9th Circuit Court of Appeals to be incredibly rewarding, and by sharing with students why it was transformative for her, she encourages them to take on the difficult task of applying for clerkships.

She also has enjoyed mentoring students through directing paper projects, in part because she knows how important the help of her professors on her graduate school research projects was to her growth as a scholar. She especially likes working closely with students who want to do empirical or statistical research. She guides them through the process, from identifying important questions where the theory does not predict what is going to happen, to being a responsible researcher and making sure their methods support their conclusions.

Maciá also takes very seriously her role in encouraging women who are interested in antitrust and corporate law because women have traditionally been underrepresented in those areas. She believes she makes a difference by being a woman and teaching in this area.

“It is easy to be subconsciously affected by representation. If you have a group of people in certain areas that are all different from you, then that can affect whether you think you can do it. I am happy to provide an example to young lawyers of a woman who is excited by antitrust and corporate law,” she said.

She also has thought carefully about why it might be that women are underrepresented in these areas of the law and has tried to structure her classes to be responsive to these dynamics.

“Both antitrust and corporate law can involve a lot of economic jargon and numbers, and women are underrepresented in economics and math majors. My classes give students a chance to catch up, so that a lack of previous training doesn’t have to keep them out of these areas of law. And this is especially helpful to women students given the underrepresentation problem.”

She teaches the classes in a way that gives students an opportunity to get comfortable with the economics and the numbers no matter what their background is, and she assigns problem sets — which is unusual for a law class — to give students a chance to build up their confidence. She draws on her experience going into college underprepared in math and remembering how important practice problems were for her catching up: “If you practice, you will gain confidence.” One of the highlights for her of her time at Notre Dame has been spending many office hours working through these problems with some of her women students and seeing them go from being intimidated in the beginning to becoming very comfortable in this area.

Maciá and her husband have two young children, and she finds the Law School very family-friendly, a key factor in her decision to come here. “I have learned from mentors at the Law School who are fully committed to their vocations as parents, spouses, scholars and teachers and show me how to excel in all of these roles.”

She wants to be a strong role model for her children. It guides her work and encourages her to work harder. “I think of my parents coming home happy from their jobs and excited about the impact they were making. The example they set for me was so important — they showed me what a gift it is to know that you are doing something that makes a difference. I hope to be able to model the same for my children.”